Last week, Disney+ released a restored version of The Beatles Anthology, the landmark 1995 ABC eight-part documentary series that remains the closest thing to a definitive account of the band’s extraordinary journey. I binge-watched the updated Anthology over the Thanksgiving holiday weekend, which brought back memories of watching the original with my parents 30 years ago. Now I’m the parent, though my wife and four-year-old son were less enthusiastic about the marathon viewing sessions.

Last year, I wrote an essay for Cato’s Defending Globalization project examining the globalization of popular music, with the Beatles as a central case study. While I enjoy the band’s music and appreciate their role in music history, I’m no super fan. As a researcher focused on international exchange, however, the Fab Four’s story is a groundbreaking example of the enduring benefits of cultural globalization and the tremendous reach of today’s truly global music market.

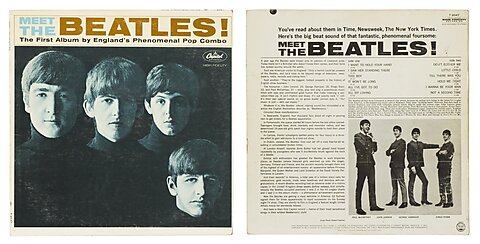

Watching the restored footage of four working-class young men from Liverpool, England—who cut their musical teeth playing in the port city of Hamburg, Germany—navigating screaming airport crowds and sold-out stadiums across continents, one is struck by just how revolutionary their global reach was, especially given the technological limitations at the time. When 73 million Americans tuned in to watch the Beatles perform on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964, they were witnessing something genuinely new: a British band achieving instantaneous cultural dominance in the world’s largest consumer market that had, until then, largely shunned foreign music. The Anthology captures these moments and many similar ones with remarkable intimacy, demonstrating how Beatlemania quickly transcended national borders.

The Beatles both benefited from and helped shape cultural globalization. Thanks to the penetration of American music into British radio markets, the band drew from American rock and roll, blues, and rhythm and blues—genres created largely by black musicians who had fused musical elements from the Americas, Europe, and Africa. John, Paul, George, and Ringo also absorbed French existentialism. After a long stay in 1968 in Rishikesh in Northern India to study at the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, meanwhile, they began incorporating Indian instrumentation and spiritual practices into their work. They brought Western attention to Eastern spirituality while channeling American musical traditions through a distinctly British sensibility.

Perhaps more importantly, the Beatles established the template that global artists follow to this day. When Taylor Swift crashed Ticketmaster France’s website with overwhelming demand in 2023, she was walking a path laid out six decades earlier. The infrastructure of global stardom—international touring, coordinated album releases, a worldwide fan base united by shared devotion—was pioneered by the lads from Liverpool.

The timing of this restoration feels particularly apt. In an era when protectionist sentiment has grown louder, with politicians around the world questioning the value of international exchange, the Beatles’ story offers a powerful counter-narrative. Cultural globalization has long since escaped the bottle, and music demonstrates why that’s worth celebrating.

Consider what streaming platforms have done to accelerate musical globalization since the original Anthology aired three decades ago. Latin American artists now routinely top global charts. K‑pop acts sell out American stadiums. A teenager in Tokyo and another in Toronto can discover the same emerging artist simultaneously. Music has become more accessible and more diverse than at any point in human history, with services like Spotify (a Swedish company) exposing listeners to styles and sounds they might never have encountered in an earlier era.

None of this would be possible without the cross-border exchange of ideas, capital, and creative works that globalization enables. Music streaming doesn’t respect tariff walls or trade barriers. Even if protectionist politicians succeeded in restricting the flow of certain physical goods, cultural globalization would march on.

At its best, music has always been a blend of cultures and influences and a form of human expression that builds bridges and breaks down barriers between people who might otherwise have little in common. Indeed, the Beatles’ story is a triumph of globalization and a poignant example of what is possible when borders are relatively open to people, ideas, and art.